Trust can be measured in the strength of a bungee cord, the packing of a skydiver’s parachute or entrusting a Sherpa to lead you to the top of Mount Everest.

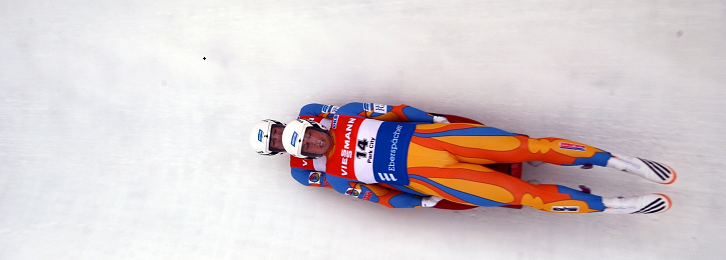

What kind of trust would you need to have to lie on your back on a small sled, have another guy lie on top of you and then thunder down an ice tunnel at 80 mph plus – not being able to see where you are going! Welcome to the sport of double luge!

Over the past two weeks I’ve stayed up past my bedtime to watch the Olympics. I was fascinated by the double luge races not only because of the comical sight of two men lying on their backs in spandex suits, but because of the level of trust that this sport requires of its participants. How would you like to be on the bottom of the pile, the “slider†who trusts in the pilot to safely steer them thru the 14 or more curves to the finish line. If you’ve ever watched the sport you would have noticed that the guy on the bottom can’t see where he is going; he’s just along for the ride – and the additional weight he brings to the team!

The sport of luge goes way back to the 16th century and comes from the French word for “sledgeâ€. The first international competition was held in Switzerland in February 1883. The four-kilometer race between the Swiss resorts of St. Wolfgang to Klosters, had 21 competitors representing six nations. The winning time was 9 minutes, 15 seconds. Luge became and Olympic sport in 1964 in Innsbruck, Austria.

Double lugers enter the race on a sled that weighs between 25 and 30 kilograms. The total weight of sled and two competitors can weigh a maximum of 180 kilograms. If the team doesn’t reach the weight maximum, they can carry weights on their body. And yes, they do have to weigh in.

Lugers endure forces up to five times that of gravity and because of the position of their head; the pilot has difficulty seeing where he is going. His partner doesn’t see the track at all and takes his instructions from the way the pilot tilts his head.

This is a very dangerous sport and one wrong move can hurtle the sled, along with its riders, out of the track. Luger Nodar Kumaritashvili of Georgia was killed during a practice run at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics.

In his book “The Five Dysfunctions of a Teamâ€, Patrick Lencioni says that Trust is foundational to the success of a team. If trust is absent from the team it will have a high level of dysfunction and ultimately fail.

In researching the topic of trust I came across two very good articles, one by Robert Hurely (The Decision to Trust) and the other by Paul J. Zak (The Neuroscience of Trust). Both articles are posted in this newsletter.

Hurley’s Trust model was developed for the workplace but many of his points can also be applied to a double luge team. People with a high-risk tolerance will trust others easier. Those with a low tolerance for risk often don’t trust others or themselves. So a luge team that hits hairpin turns at 80 miles an hour, especially for the colleague on the bottom of the pile, will most likely have a very high tolerance for risk .

Trust is also built because the teammates have many things in common. This could include:

- Love for the same sport

- Work ethic

- High level of competence in carrying out their role

- Putting the interest of the teammate first

- Same university or sporting club

- Predictable behaviors

- High level of integrity

- A trainer that they respect and look up to

- Very good communication skills both on and off the track (non-verbal communication is a strength)

Paul Zak is the founding director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies and a Professor of Economics, Psychology and Management at Claremont Graduate University. Professor Zak summarizes his research findings as follows:

In my research I’ve found that building a culture of trust is what makes a meaningful difference. Employees in high-trust organizations are more productive, have more energy at work, collaborate better with their colleagues, and stay with their employers longer than people working at low-trust companies. They also suffer less chronic stress and are happier with their lives, and these factors fuel stronger performance.

Professor Zak’s research is based on measuring the brain activity of people while they are working to see the level of Oxytocin that the brain is producing. Oxytocin is a peptide hormone and neuropeptide and according to Zak, it “reduces the fear of trusting a stranger.†Mothers of newborns also have higher levels of Oxytocin and this helps in the bonding process.

Zak’s research in organizations and with teams has shown that the two key drivers of trust are good communication and recognizing excellence. People working in high-trusting companies are 70% more aligned with their company’s purpose, feel 66% closer to their co-workers and were less likely to experience burnout. A final interesting finding that Zak made was that employees who work for high-trusting companies earn on average $6,450 more (17%) than works at low-trusting companies.

I don’t know if this article sparked your interest in double luge but trust me, my level of risk tolerance is much too low for a ride on a luge sled, a jump out of a plane or even a bungee jump from a bridge.

Sources:

Patrick Lencioni: “The Five Dysfunctions of a Teamâ€, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, 2002

Robert Hurley: The Decision to Trust, HBR Sept. 2006

Paul J. Zak: The Neuroscience of Trust, HBR Jan-Feb. 2017